Some mornings, your body surprises you.

Other mornings, it reminds you of its limits.

For people living with autoimmune conditions, life rarely follows a predictable rhythm. A day that begins with energy and optimism can shift into fatigue, pain, or brain fog with little warning. And no matter how much is planned — work, exercise, social plans — the body sometimes has other ideas.

This unpredictability can be one of the hardest parts to live with. It can shape confidence, relationships, and even identity. When the body feels uncertain, the rest of life can begin to feel uncertain too.

When Life Becomes Unpredictable

Autoimmune conditions don’t always make themselves visible. The changes are often internal — inflammation, immune overactivity, exhaustion — yet their impact is far-reaching.

Many people describe the experience as constantly negotiating with their own body: “Will I manage this today?” “Should I rest now or push through?”

This constant adjustment takes energy in itself. Plans may need to change last-minute. Symptoms can flare without clear cause. The mind wants clarity; the body offers variability.

Emotionally, this can lead to frustration, guilt, or a sense of lost control. You may question your reliability or feel as though you’re letting others down — when, in reality, you’re navigating a complex, unpredictable condition the best way you can.

Learning to live well with unpredictability often begins by redefining what “control” really means. It’s not always about controlling outcomes — it’s about cultivating steadiness within them.

Pacing: The Foundation of Living Well

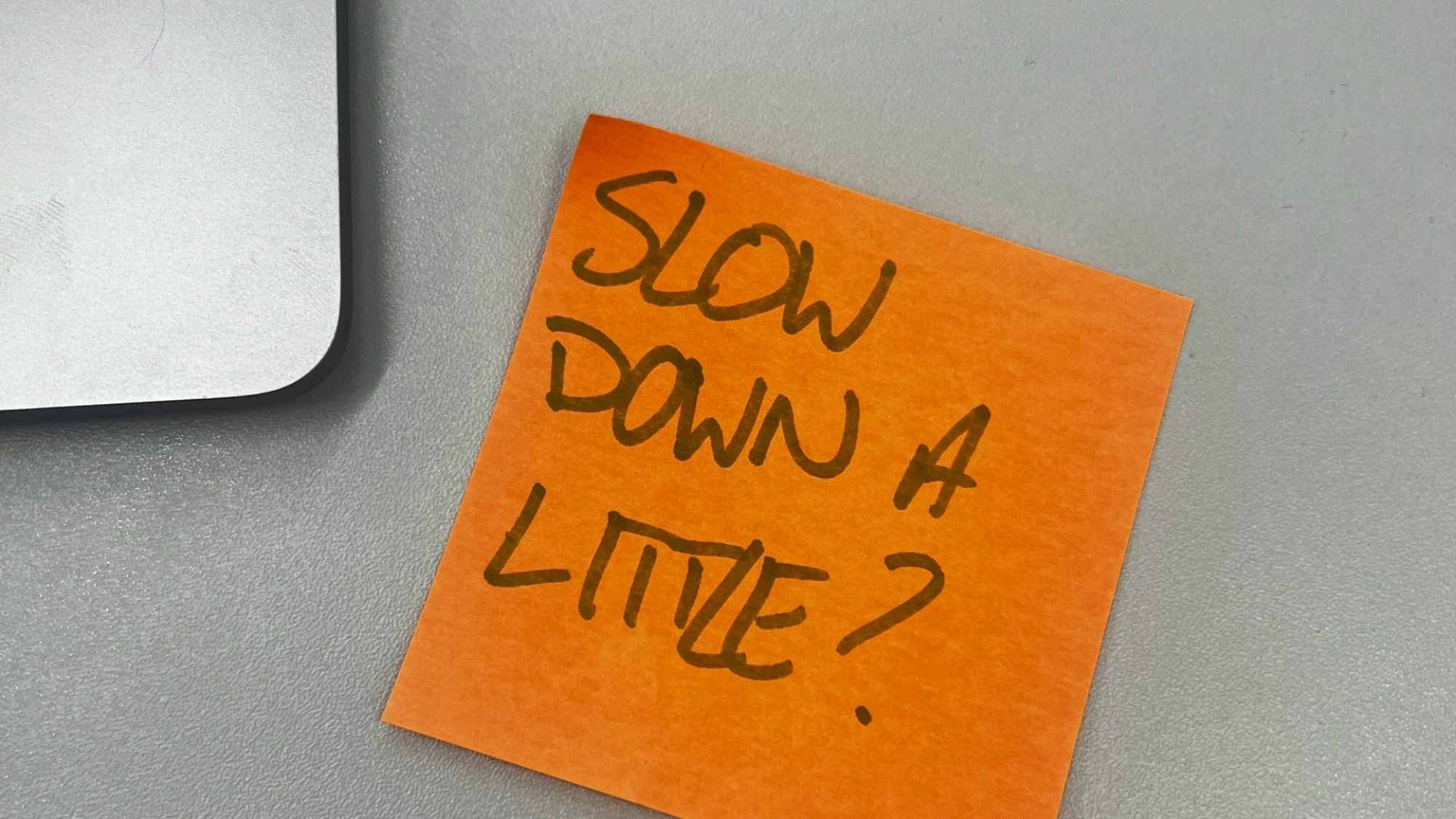

Pacing is one of the most powerful yet misunderstood tools in managing long-term conditions.

It isn’t about doing less — it’s about doing what matters, sustainably.

Think of pacing as a rhythm rather than a restriction. It’s the art of distributing energy with awareness, of balancing activity and rest before exhaustion sets in.

For me personally, pacing didn’t come naturally.

With ADHD, my instinct was always to do more — to fill every moment, to rush from one idea to the next, to equate movement with progress. Slowing down felt uncomfortable, almost unnatural at first.

It took years of practice (and many bad days and weeks) to realise that rest is not a reward for productivity — it’s the foundation that makes everything else possible.

Learning to pace required as much emotional work as practical planning. It meant noticing when I was pushing out of habit rather than intention. It meant accepting that energy fluctuates — and that’s okay. Now, pacing feels less like a rule and more like an act of respect toward my body and mind.

In coaching, pacing often begins with noticing patterns:

-

When does energy naturally peak and dip throughout the day?

-

Which activities feel restorative, and which are draining?

-

How do stress, sleep, and nourishment influence symptom stability?

Once that awareness builds, pacing becomes less about “stopping” and more about “adjusting.” It might mean alternating physical and cognitive tasks, breaking projects into smaller steps, or scheduling recovery time as non-negotiable — not as an afterthought.

There’s also a psychological side to pacing. It can challenge old beliefs — like “rest is lazy” or “I should be able to do more.” Learning to pace well often involves replacing self-judgment with self-respect. It’s about honouring what the body communicates, even when the mind wishes it were different.

Acceptance: Finding Peace in the Space Between Doing and Being

Acceptance is often misunderstood as resignation. But in reality, acceptance is an active, empowering process.

It’s the shift from fighting the body to working with it.

Acceptance doesn’t mean liking the situation or giving up on improvement. It means acknowledging what is happening without layering on blame, shame, or resistance.

When energy fluctuates, acceptance sounds like: “Today is a low day — I’ll adjust,” rather than “Why can’t I be stronger?”

Psychologically, this mindset aligns with approaches such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), where the focus is on choosing actions that align with personal values, even when discomfort is present. It’s about directing energy toward what brings meaning rather than getting caught in what we can’t control.

In practice, this might look like saying no without guilt, redefining productivity, or simply allowing rest without explanation.

Over time, acceptance brings a sense of steadiness — not because symptoms vanish, but because resistance softens.

Balancing Pacing and Acceptance

Pacing and acceptance are often intertwined.

Pacing helps manage the external — how energy is spent.

Acceptance supports the internal — how one relates to the body and to change itself.

Together, they create a foundation for self-trust. They allow individuals to plan with flexibility, live with more kindness toward themselves, and find a rhythm that fits the life they actually have — not the one they wish they still did.

This approach doesn’t remove unpredictability, but it helps to navigate it with less fear and more stability.

In a world that values speed, learning to live at your own pace is an act of quiet strength.

A Gentle Pause for Reflection

Living with an autoimmune condition is an ongoing negotiation — between hope and patience, between body and mind, between plans and possibilities.

Each day may look different, but each one offers a chance to practise gentleness and adaptability.

If you’d like to pause and reflect, here are a few prompts to guide your thinking:

1) What does “control” mean to you now — and how has that definition changed since your diagnosis?

2) How might you use pacing not as a limit, but as a way to protect what matters most to you?

3) What would acceptance look like today — in your thoughts, your schedule, or your self-talk?

Leave Your Comment